Rebel Yell! Are You Joining the Reader’s Resistance?

Image credit: public domain

An invisible war is taking place around you, unnoticed by all but its most dedicated partisans. Despite one side repeatedly declaring victory, their opponents fight on with undaunted will.

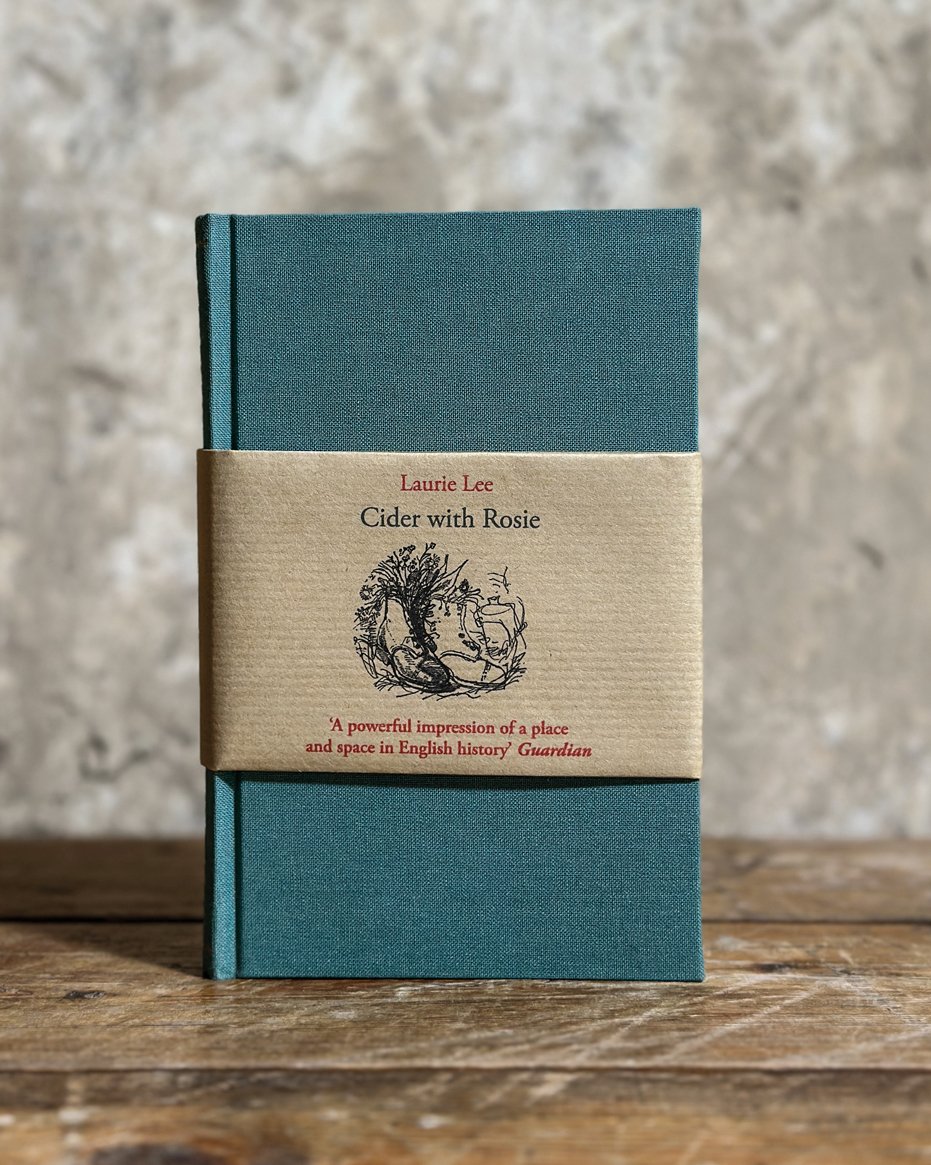

Faber Member Editions: high-quality hardback books available exclusively to Faber Members. Image credit: Faber and Faber

You may be reading this article on your phone or laptop, but you have the chance to play your part in the future of print.

Simon Armstrong, founder of online bookstore Errant Books and formerly Tate’s Head of Book Sales and Buying, is one of print’s most ardent defenders. ‘The idea that everyone was going to buy a Kindle or a digital device was catnip to investors,’ he says. ‘But nobody talks about e-readers anymore.’

His experience bears out this fact. ‘At Tate, we sold two books a minute. As long as we were open, we were selling books,’ he says. ‘Thousands and thousands of people are waiting to buy.’

If anything, digital has made traditional publishing more competitive. ‘More attention’s being paid to the design of physical books,’ explains Toby Faber, a non-executive director of Faber and Faber and grandson of the company’s founder. ‘Even the meanest mass-market paperback still has a certain quality that you can’t reproduce. Design is crucial, and we design everything.’

‘As long as we’re open we’re selling books.’

Even ‘trivial’ aspects need attention. ‘We make sure to print our poetry on presses where the paper is fed through the right way round,’ Faber says, ‘which ensures that the book falls open in your hand in just the right way.’

Tech companies are quick to emphasise print’s inconveniences, but there are tangible advantages to the physical. Faber shares that he’s reading a fantasy ebook to his daughter featuring a world map. In a hard copy, he’d be able to flip to that page easily, but in an ebook it’s a nuisance.

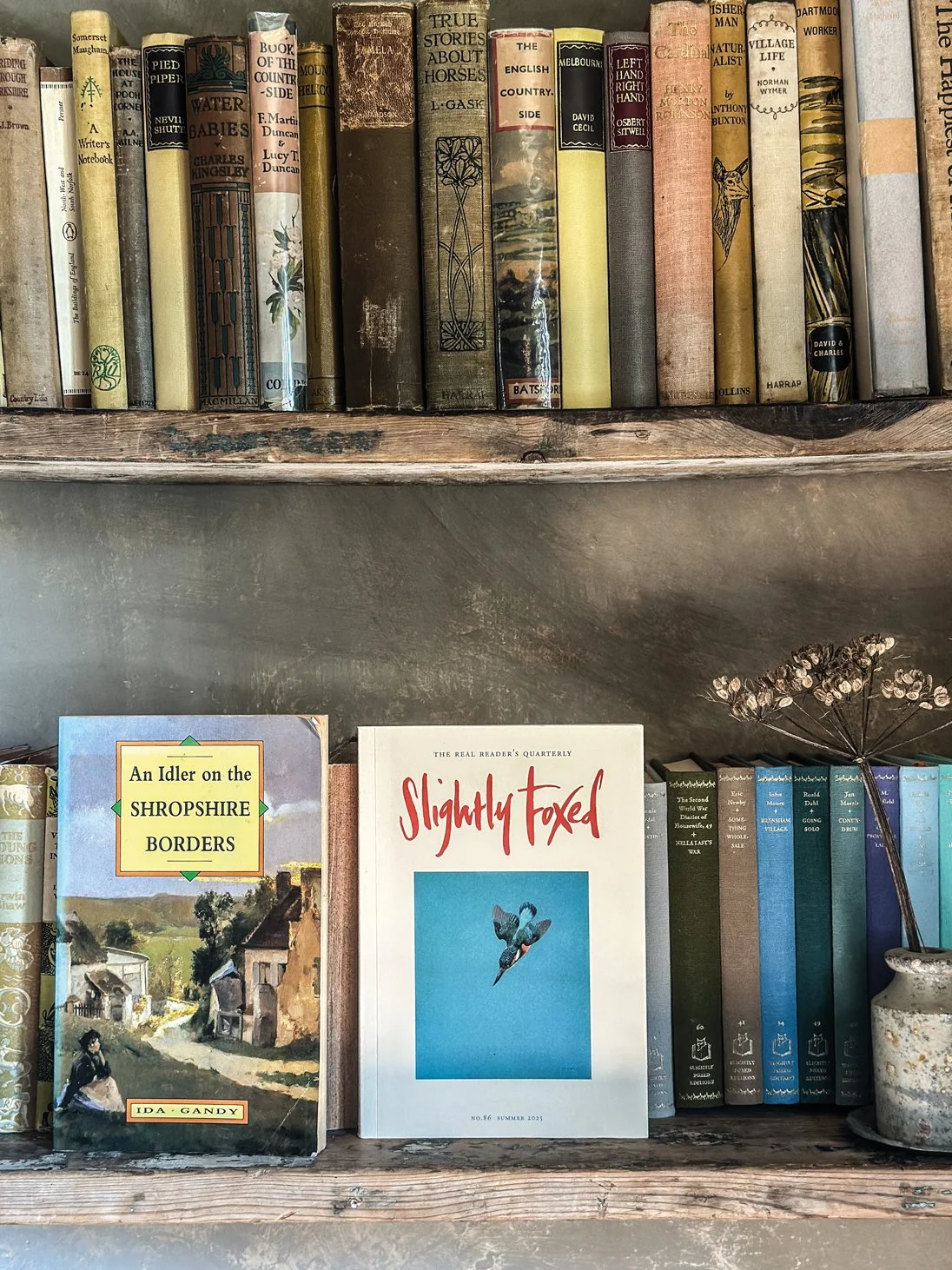

Image credit: Slightly Foxed

‘People don’t realise how important it is to have a good clear typeface, or a reasonable amount of space between each line so the eye can move smoothly,’ adds Gail Pirkis, editor and co-founder of Slightly Foxed, a quarterly literary magazine that also reissues editions of classic books.

‘Design is crucial, and we design everything.’

Information gleaned digitally, interrupted by ads and unwanted videos, seems to evaporate; in contrast, Pirkis believes (and science proves) that the brain engages better with print.

‘We take great pride in designing our magazines and books to provide physical pleasure,’ she says. This clearly pays off: Pirkis says the magazine has 8,000 subscribers and growing. They also produce quarterly podcasts focused on particular genres or writers (to prepare for their next instalment, she’s reading lots of Muriel Spark).

‘Find a printed book that you’ve enjoyed, sit down with it quietly, and give yourself half an hour of reading,’ she advises. ‘Once you start, you’ll be hooked.’ If you can’t spare half an hour, even six minutes of reading is good for you. Research by the University of Sussex shows that your stress levels lessen by 60% in that amount of time, an even bigger decrease in stress than having a cup of tea.

Image credit: Slightly Foxed

Pirkis also preaches revisiting old favourites as a crucial weapon in the book-lover’s arsenal. So much of what’s online is discarded as quickly as it’s consumed—how often do you find a tweet or a LinkedIn post worth rereading in depth?—but print is harder to cast aside. Crafted for long- term appreciation, it’s a counterattack on our throwaway culture.

‘Give yourself half an hour of reading. Once you start, you’ll be hooked.’

Sci-fi and fantasy novelist Ian Green agrees heartily. ‘I still have my old Iain M. Banks paperbacks, and barring fire or flood I probably always will,’ he says. ‘I treat my books poorly, cracked spines and folded pages, stick them into back pockets and the bottom of bags. Having a book I can pull from a pocket anywhere is a joy.’

Green enthuses over how his publisher, the Bloomsbury imprint Head of Zeus, is always excited to hear his ideas on book design, with skilled illustrators bringing his vision to vivid life.

‘Years later, seeing copies of my books in my favourite bookstores always makes me smile,’ he tells me. ‘That’s exactly how I found so many books that were impactful in my life. Being a part of that chain is wonderful.’

Image credit: Slightly Foxed

You’ll hear a lot of doom-and-gloom stories about the decline of bookshops. While there’s some truth to this, it’s far too soon to say we’ve lost to the forces of Amazon and its ilk. ‘A thriving high street doesn’t just need a good dentist or doctor—it needs places where people can interact. Bookshops bring a lovely synergy to a town,’ says Fleur Sinclair, president of the Booksellers Association and owner of Kent’s Sevenoaks Bookshop.

While she’s concerned about financial factors that make life difficult for bricks-and-mortar, her shop continues to host an ambitious calendar of author events featuring everyone from non-fiction nature writers to bestselling novelists.

‘The beauty of a bookshop is that it’s a space where you can be open.’

‘It’s this human-to-human connection that enhances a reader’s experience,’ she says. ‘It builds a community: you sit in a room with like-minded people who’ve all turned up because of how much an author’s work means to them. The beauty of a bookshop is that it’s a space where you can be open.’

It’s easy to overlook the peace and connection that books provide. Simon Armstrong shares how he grew up in the Northeast of England in the Eighties, in an environment obsessed with ‘football, casual violence, alcoholism, and cars.’

‘I knew there was more to life than that,’ he says. Armstrong found new worlds through music and print. Hanging out in record shops and secondhand bookstores, he was surrounded by classics and people publishing free magazines like Sleazenation.

‘There’s an almost religious shame about being online all the time, and that sells books—I literally sell books about that.’

Image credit: Slightly Foxed

These early encounters sparked his love – and intrinsic understanding – of the power of print. ‘People are constantly returning to what’s handmade and hand-drawn,’ Armstrong says. ‘Why? Because people have a huge amount of guilt. There’s an almost religious shame about being online all the time, and that sells books—I literally sell books about that. People come back to print to feel calm.’

It’s easy to surrender to a digital future—and yet most of us haven’t. Maybe you’re a regular at independent bookstores, or revisit old books on your shelf. Perhaps you even subscribe to LOST ART’s print version (in which case you’re our favourites!). But most of us, in some small way, want to swim against the tide of technology and the false convenience it promises.

‘People come back to print to feel calm.’

Deep down, we know Armstrong is right. We do have guilt about being online. It’s material things that keeps us sane, and the enduring pleasures of print are evidence that we need our bodies to stay grounded in this world, while our imaginations roam free in the universes that authors construct. Ignore the power of the book at your peril.