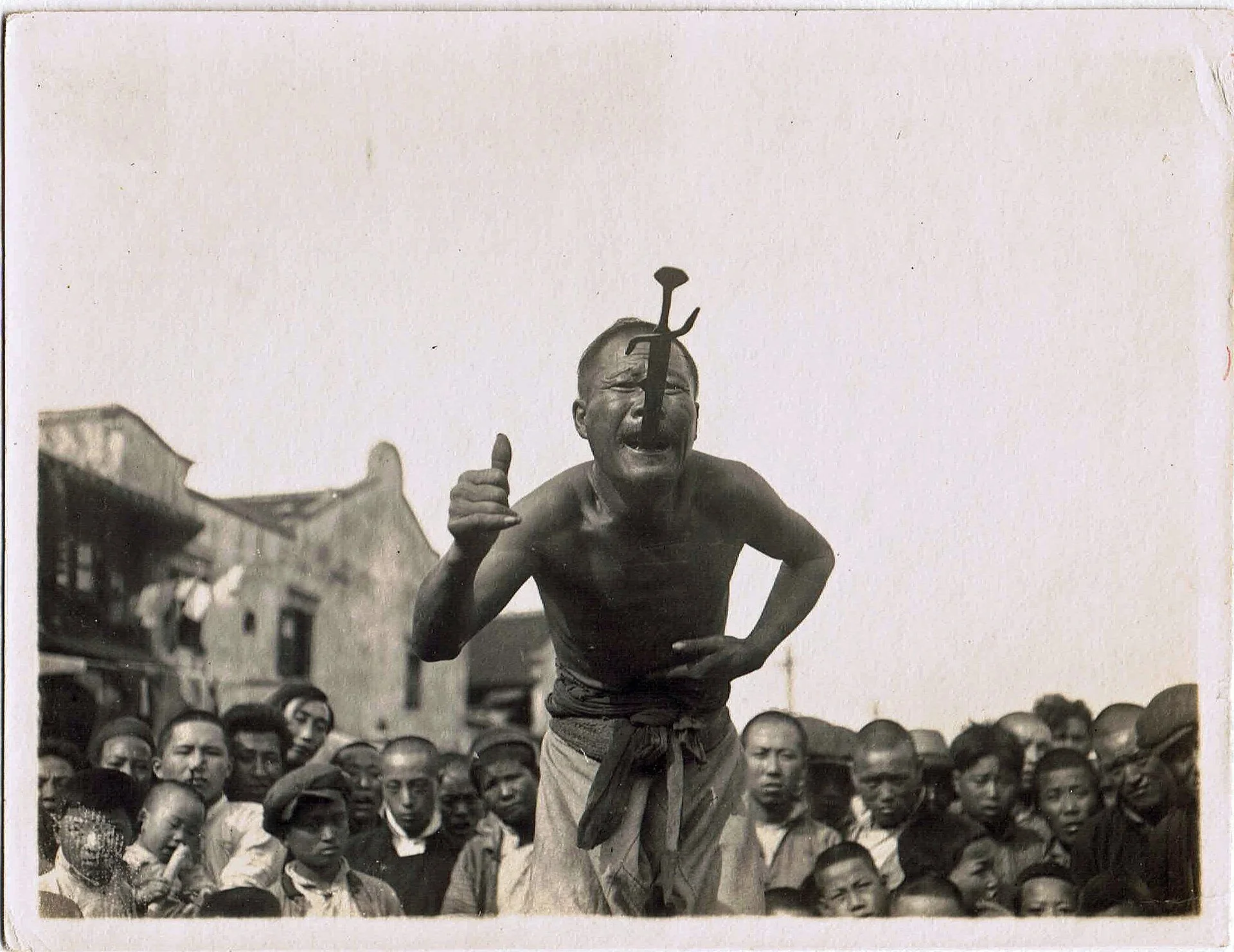

Sword Swallowers are a Dying Breed, But Not For The Reason You Think

Sword swallowing in China, circa 1921. Image credit: public domain via Wikimedia Commons

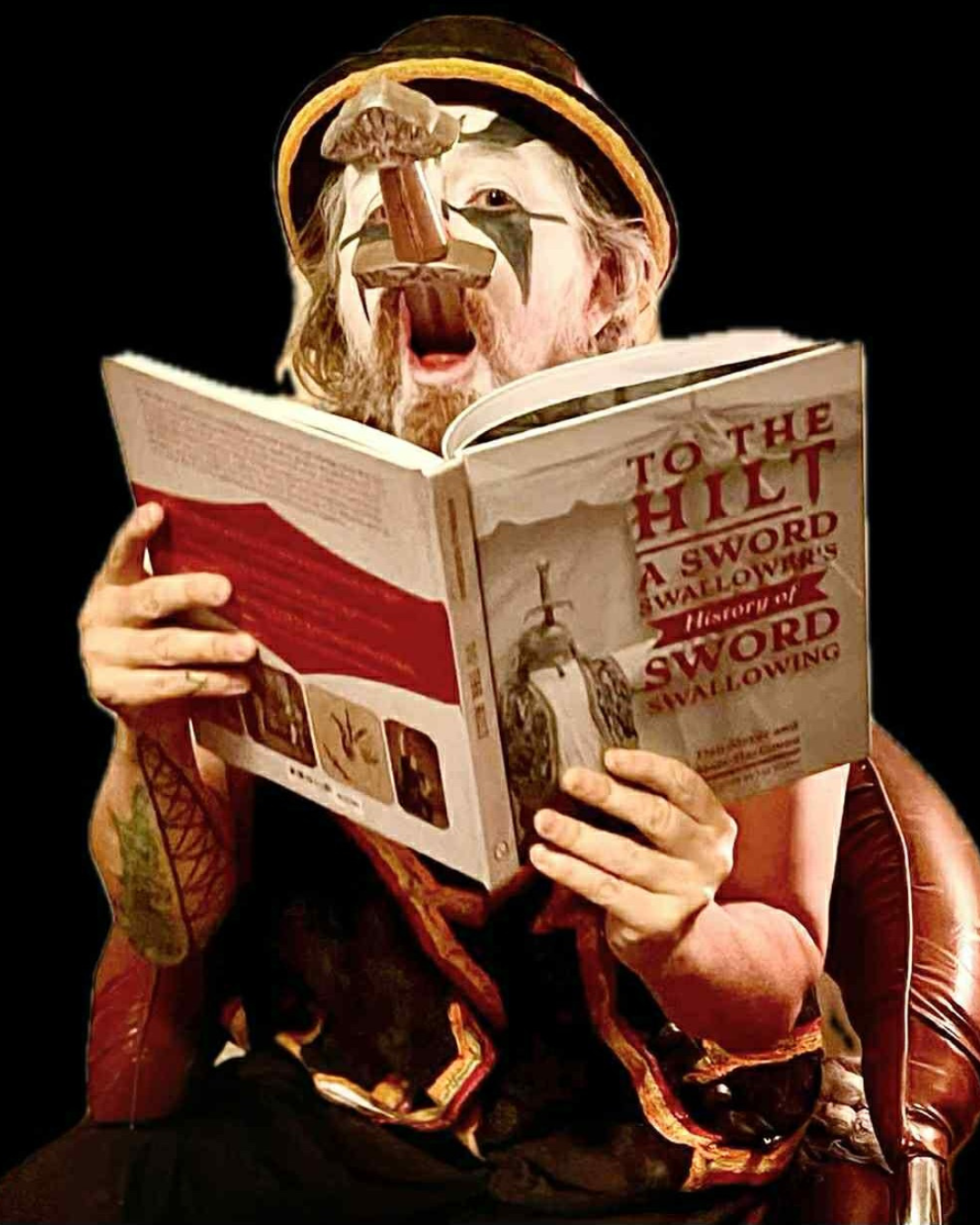

‘There’s a code among sideshow performers,’ says Jelly Boy the Clown, ‘I had to earn my mentors’ trust.’

Jelly Boy practices sword swallowing, an ancient and spectacular stunt that’s pretty daring, to say the least. But while intended for public show, the central paradox in sword swallowing is that very little is known about it.

Image credit: David Hashim

Sword swallowing isn’t a magic hoax; it does what it says on the tin. You pick up the weapon, tip back your head, and slide the blade down your throat. What happens internally involves terms more commonly used in an autopsy. To swallow a sword you must align you mouth and epiglottis, open your epiglottis, suppress the peristaltic reflex, guide the blade between the lungs while slightly shifting your heart to the left, pass the blade through the diaphragm, and relax your lower esophageal sphincter to bring the blade down to the stomach. Please, don’t try this at home.

‘I had to earn my mentors’ trust.’

While feasible, it is extremely dangerous. In the past 150 years, there have been around thirty deaths related to accidents involving professional performers. Slight pressure can cause agony, and a mistake might puncture an organ or end a life. ‘You have to put your body in harm’s way,’ sideshow performer and street artist Viscera Nefarious says. ‘You do have to accept a certain amount of risk, and that’s not something you can fake.’

Despite the risks, it’s an ancient art that has survived for millennia. Sword swallowing began in India circa 2000 BC, passed through ancient Greece, and meandered across the Eastern and Western world, eventually finding itself at 19th-century sideshows and 20th-century amusement parks like Coney Island. Most recently, this age-old skill has been beamed into our living rooms via shows like America’s Got Talent. And yet, very little has been written about it.

This secrecy seems at odds with the showmanship, though it’s in part because sword swallowing can’t be learned from a manual or an anatomical diagram. It’s an embodied skill, passed from mentor to apprentice through direct practice and gradual adaptation of the body. Before they spend hours and hours with an apprentice, demonstrating dangerous skills that demand hands-on repetition and observation, mentors need to be selective. They’re not just looking for persistence, but also the right attitude towards risk and the art form’s demands. Teaching sword swallowing is both a technical and moral responsibility. Furthermore, they need to be able to challenge the audience’s disbelief. As Jelly Boy remarked after his America’s Got Talent appearance, ‘Tricks are for kids. I do stunts.’

Image credit: Sean Scott

Unsurprisingly in such high-stakes conditions, a bond develops between the master and student. ‘When you teach someone sword swallowing, they become part of your family,’ says Alaska, an aerialist and sword swallower at Coney Island. ‘When you become part of the circus or the sideshow, it’s your new family because they understand the unique struggles that come with this lifestyle.’

‘Tricks are for kids. I do stunts.’

Jelly Boy’s teachers passed down a host of skills, from essential health and safety, to how to weld his own swords. ‘I had two main mentors. One was Red Stuart, he’s in his seventies now and he travelled with carnivals in the 1960s. The other was Enigma,’ he says. ‘Those guys aren’t going to tell anybody anything unless you show them you have what it takes to add something to the art form.’ And it’s not just about avoiding competition: ‘They don’t want to cheapen [sword swallowing] by showing someone who isn’t a good presenter, who’s crazy, or who’s just out for attention.’

After all, there’s more to this craft that getting the blade down your throat: it’s also about presentation. Mentors can demonstrate physical techniques, but it’s up to every performer to develop their own act. Some will invite audiences to check the swords to prove they’re solid, or ask spectators to remove the blades from their throats. Some swallow curved swords or light-up neon blades that show exactly where they are in their body. Sword swallower Zora Van der Blast pushed this even further by performing while visibly pregnant.

Image credit: Jim R Moore

All of this is to overcome the audience’s instinctive disbelief. Unless we’re not feeling well, we don’t spend much time thinking about our organs. The internal workings of our body are silent; we barely sense the throat or ponder the exact position of our esophagus. Meanwhile we easily react to anything happening on the surface of our body. That’s why some sideshow acts such as the pin cushion (inserting needles under the skin) or the blockhead (putting a nail into the nose) are instinctively shocking. But the sheer strangeness of sword swallowing makes some viewers assume that it’s fake. The challenge for the performer is to push against this innate cynicism without abandoning safety or losing mystique.

‘They don’t want to cheapen [sword swallowing] by showing someone who isn’t a good presenter, who’s crazy, or who’s just out for attention.’

Once spectators accept it’s physically real, they stop looking for the sleight of hand and start seeing the danger. Fascination intensifies as the body, perceived as fragile and limited, demonstrates its capacity for the unimaginable.

But the secrecy behind sword swallowing could also be a threat to this art form. With the decline of circus attendance in the 21st century, its few remaining practitioners are now working to preserve its heritage. To The Hilt: Sword Swallow, founded by Dan Meyer in 2001, is working to promote this art worldwide with events such as World Sword Swallowers’ Day celebrations (celebrated on February 22nd, in case you’d like to make a note for your calendar)—in 2013 Meyer celebrated this occasion by swallowing an 18-inch sword, then pulling a 3,700-pound Mini Cooper attached to the sword. He’s even published To The Hilt, a history of this art form co-authored with Marc Hartzman.

People like to talk about art forms in decline: how digital photography displaces the use of film, or the challenge that ChatGPT poses to literature. Sword swallowing, on the other hand, is far harder to take into the virtual realm. You need a real flesh-and-blood body, and you also need an unshakeable bond between mentor and student that cannot be mediated by a screen. Perhaps, as people turn away from tech, such visceral —yet totally authentic—skills may experience a resurgence. The only problem that I can foresee is a chronic shortage of teachers.