Labour of Love: The Women Destigmatising Childbirth in Art

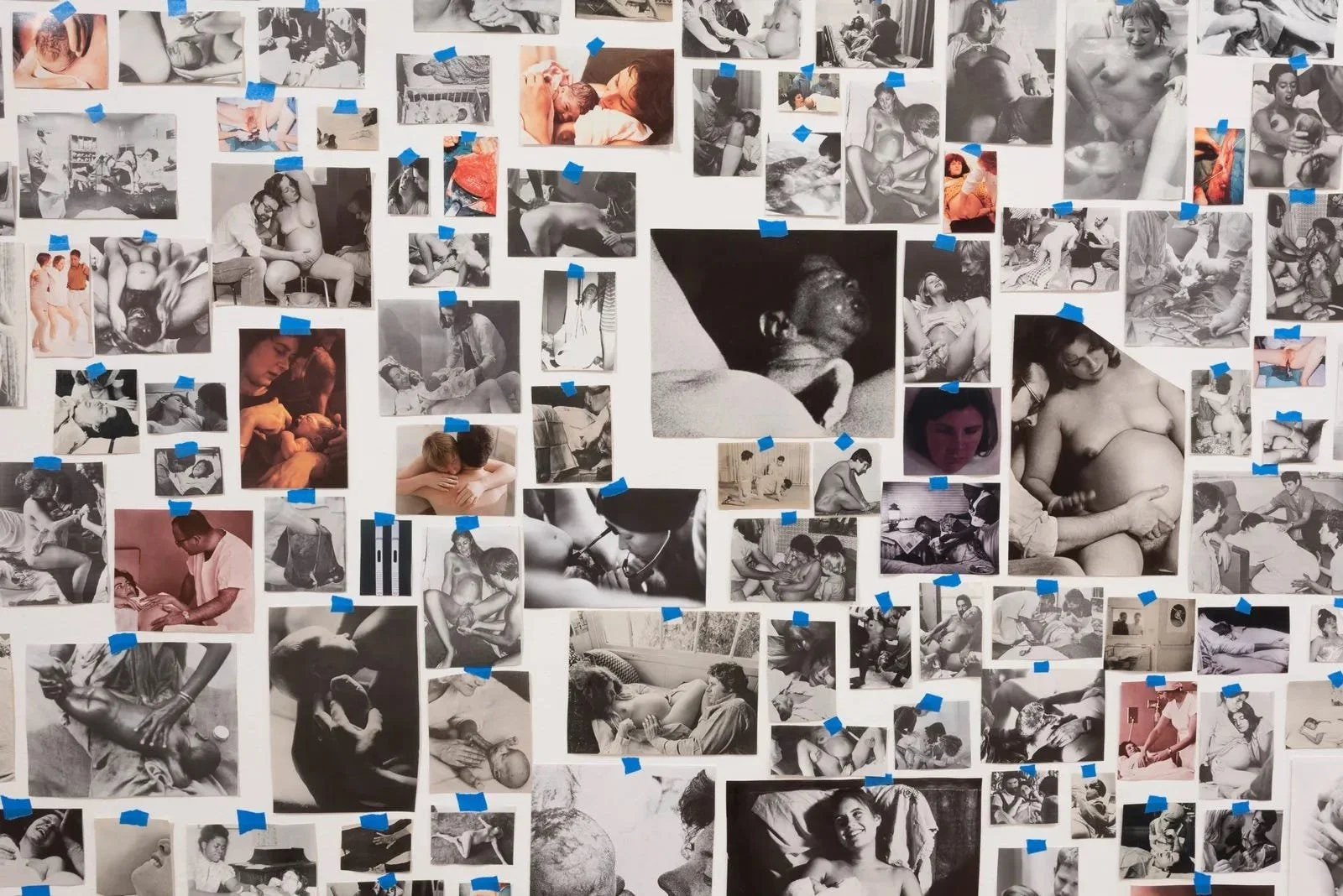

Carmen Winant’s My Birth (detail), 2018. Site-specific installation of found images, tape. The Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Kurt Heumiller / © 2018 Carmen Winant

One of my most visceral teenage memories is turning on Channel 4 after 10pm and finding myself confronted with One Born Every Minute – the only British TV show bold enough to drag cameras into NHS wards and record, in detail, hundreds of women giving birth.

I was astounded; the blood, the sweat, the sheer bravery. I had never seen anything so corporeal or exposed. Who can blame me? Where was I ever meant to have seen a newborn crowning, for instance? The education on the ‘miracle of life’ I received at school presented a highly sanitised animation of a baby gliding seamlessly through a completely hairless vagina.

Caravaggio’s The Adoration of the Shepherds (1609). Image credit: public domain via Wikimedia Commons

One occasionally looks to the galleries for traces of the human experience, but I hadn’t encountered childbirth in art. There are paintings of pregnant women in droves, and women in the tender early stages of motherhood, but hardly anything depicting the messy affair in between. To birth, to labour, to push, is necessary, but seemingly unspeakable; viewers of art are not privy to such exposure. Childbirth, as Margaret Atwood expressed, seems to be the ‘Last Taboo.’

I had never seen anything so corporeal or exposed. Who can blame me?

Where childbirth has been portrayed by male artists, it has not symbolised or celebrated women’s power to create. Rather, artists have skipped over birth entirely, focusing on the moments just before or after labour. Caravaggio’s 1609 The Adoration of the Shepherds is a key example. Depicting Mary holding Jesus moments after birth, the scene is dark and unclean, bar the presence of placental, lurid red robes. Mary sits on the ground in humility; this is no holy birth (or birth at all), but a scene marked by exhaustion and human fragility.

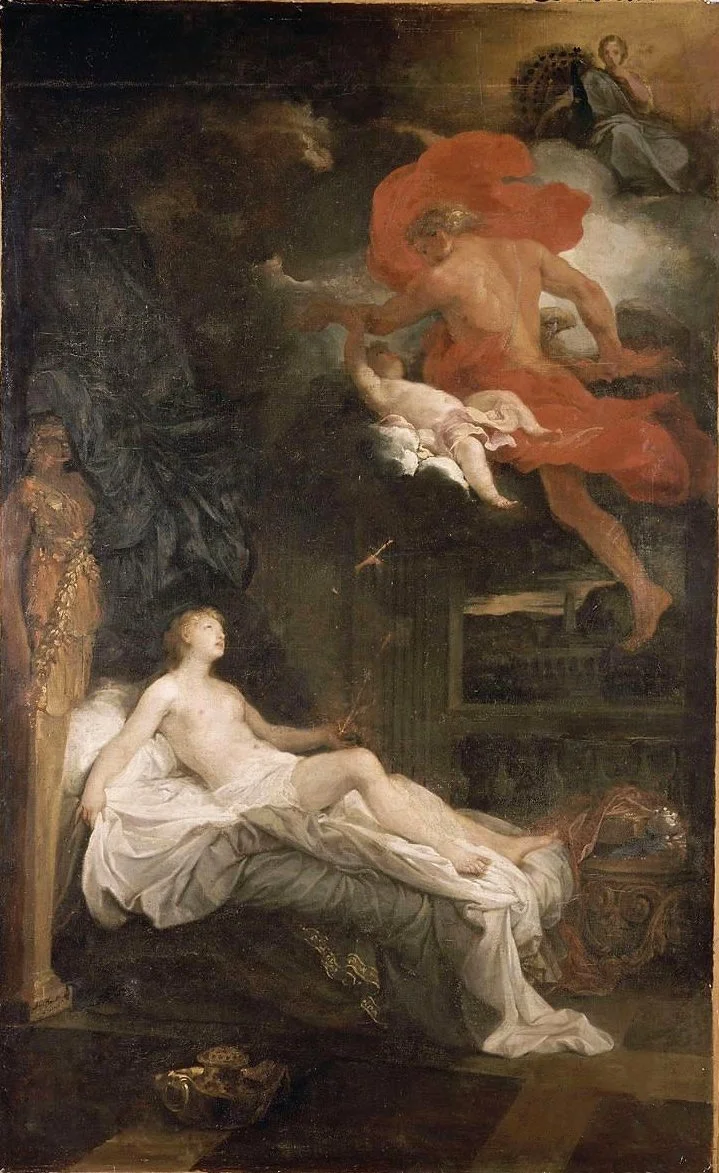

Bon Boullogne’s Semele (c.1688-1704) similarly depicts birth without labour. In this scene, Zeus extracts a baby from Semele and straps the newborn to his thigh. It is Zeus who is responsible for the life-giving process, domineering over the top-right of the frame. Women are not the primary agents of creation in these portraits. The very physical and arduous process (and the organs it involves) is hidden. As artist Hermione Wiltshire has asked, ‘why is the moment of crowning so difficult to look at, visualise and think about?’ After all, we know that art isn’t exactly scared of violence, intimacy, or martyrdom.

Bon Boullogne’s Semele (1704). Image credit: public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Only in the last decades has this absence in art begun to register as an absence at all. A new generation of women are working to drag childbirth out of the shadows and onto gallery walls. They are rupturing an artistic silence, and the historical discomfort which produced it.

‘Why is the moment of crowning so difficult to look at, visualise and think about?’

Unlike Caravaggio’s depiction of Jesus’ birth, Esther Strauss’ 2024 sculpture Crowning depicts Mary right in the moment. It is a state in which the virgin is never portrayed, so it’s the first time we see the woman revered for birthing Christ doing just that. Mary is portrayed in canonical robes, a nimbus around her head, and the viewer is confronted with the pain of her labour. Her brow furrows, her lips part, her body is splayed in the effort of birth. Crowning takes on a dual meaning as coronation and part of birth. Is she any the less regal for it?

Vandals beheaded the sculpture months after its creation. It is a reminder of the shame still projected onto the female body and the birthing process by an embarrassed culture. Prior to the beheading, one male critic branded the sculpture an ‘insult’ to the virgin. He continued, ‘True, all mothers give birth, but there is no record of anyone keeping a picture of their mother in their home portrayed during childbirth.’

Enter photographer Carmen Winant. Her installation, My Birth, was displayed at MoMA in 2018 and has been adapted into a book. Winant’s work compiles hundreds of archival pictures of women giving birth, including of her mother. It operates as a collective and personal project, disrupting cultural avoidance of birth and processing her own experiences.

‘Crowning’ by Esther Strauss, copyright held by the artist.

‘I don’t think it’s a mystery that birth has sort of been considered grotesque or embarrassing in our contemporary context,’ Winant tells LOST ART. ‘Thinking of each time I’ve seen a birth scene in popular media, which is rare, it’s not just that it’s grotesque, but we’re humiliated for her – it’s, so abject and she’s so debased, and she’s become so cruel! She’s screaming at her husband, screaming at the doctor. I don’t think I wrestled with how I inculcated those media representations of birth until I had given birth myself.’

‘I don’t think I wrestled with how I inculcated those media representations of birth until I had given birth myself.’

Winant’s installation centres the emotional experience of birth. It blurs boundaries between photography, information, archive, and sculpture. One must traverse the space, advancing on tiptoes to absorb each image of a birthing woman. The documentation of real women’s experiences that Winant has included is significant.

‘[Photography] has an ability like no other medium to capture and report, and that was really my aim in an unvarnished way’, Winant says, reflecting on the overwhelming and emotionally complex nature of her own birth. ‘That was my aim with this project – to try and make sense of my experience that was so nonsensical. Birth was so contradictory. It was a phenomenological wonderland and that made me look back at the media representations I’d absorbed and recon with them.’

‘Presentation’ by Danielle Orchard, Photographed by Paul Salveson. Courtesy of Perrotin

However, Winant does perceive a shift, ‘at least in the cultural zeitgeist which I’m embedded’, she adds. ‘I got a number of invitations in the years after the exhibition for themed projects. And almost exclusively they were all about motherhood. And don’t get me wrong, I’m interested in it but I’m just like – God, this isn’t really what the work was about. [Motherhood] felt more palatable, you know?’

What were we so scared of?

Winant is part of a new generation of women filling this gap. In paint, Danielle Orchard’s work, Presentation, depicts a caesarean section: a woman reclines on the operating table as a baby wrenches his umbilical cord from her womb. An audience looks on from both inside and outside the frame.

With a reclining female figure, the painting draws on historical visual language, the spectators evoking 18th century amphitheatre births where male physicians gathered to observe women in labour. Yet Orchard redefines these references using a muted colour palette and abstraction - the woman here is the centre of life and meaning. It is a collision between a silent past and an emerging present.

Both Winant and Orchard are mothers, working from their own experiences of childbirth. Centring and deriving work from women’s emotional experience of birth feels so novel – they are, for the first time, occupying space of central importance. What were we so scared of?