Unlikely Bedfellows: How NFTs and Museums are Forging Digital Art’s New Frontiers

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Lorna. Image credit: Lynn Hershman Leeson; Photo © ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe, Photo: Lynn Hershman Leeson

‘I think there’s a greater chance the masterpieces of the 21st century will be digital rather than physical,’ shares Robert Alice, artist, curator, and author of Taschen’s 2024 blockbuster title, On NFTs. ‘That’s where culture is most raw and exciting.’

But how would such a shift impact the hallowed halls of our museums?

The hushed atmosphere of galleries has already been splintered – we’re used to seeing screens, installations, and interactive elements as part of displays. But as Wallpaper presciently notes, with the death of the mall and decline of the high street, museums really are the ‘last great public space.’ Can they still fulfil their mission of acquisition, preservation, and stewardship in the digital age, or will they mutate into something unrecognisable?

Alice sees future magnum opuses as built on blockchain and likely created using AI. Despite being a traditionally trained art historian, this oncoming tidal wave that many fear will obliterate art as we know it hasn’t intimidated Alice. In fact, he finds it so exciting he’s made it his niche.

Here’s a quick CV: Alice creates his own works, and these have been collected by public institutions such as the Centre Pompidou and Los Angeles County Museum of Art; he’s lectured at the likes of Oxford University and Columbia; and flexed his academic muscle with his book, which is described as, ‘the first major art historical survey text’ on ‘all facets of the NFT ecosystem’.

Sarah Friend, Evolutionary Games and Spatial Chaos, Letters to Nature. Image credit: 2024 Victoria and Albert Museum, London

He is the spokesperson that NFTs (non-fungible tokens) badly need. After bursting onto our cultural consciousness back in 2021-22, NFTs have been plagued with a PR problem. Their newness made them fertile ground for scams and the backlash dubbed them ‘worthless’. But Alice is cerebral, eloquent, and gives off the distinct impression that he just knows his stuff.

‘The French are more provocative, they like to go to the edge of culture.’

And far from seeing public collections as old-fashioned or unattainable, he considers them the natural partner to digital art of all stripes. To his mind, institutions need to acquire digital arts because they will become so historically important. ‘I don’t think museums are trying to gatekeep, I see that as a commercial thing – you gatekeep because you have an economic advantage. The beautiful thing about museums is they’re not economically engaged so they go where culture is most interesting.’

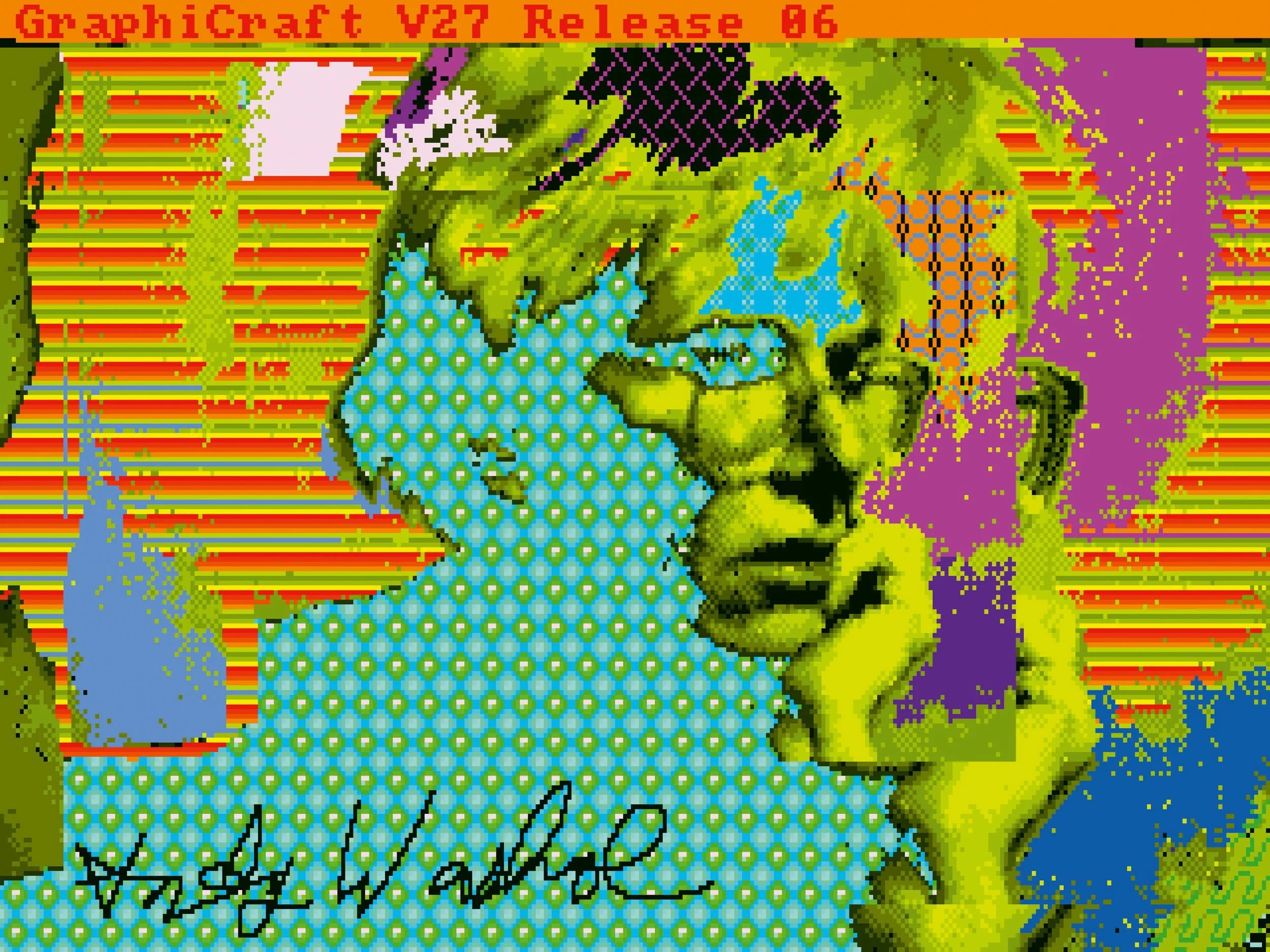

Andy Warhol, Amiga Computer Image – Andy Fright Wig. Image credit: The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by DACS/ Artimage, London 2024

‘The Centre Pompidou is leading the way in terms of building a world-class digital art chain-based collection. The French are more provocative, they like to go to the edge of culture’.

Meanwhile, to his knowledge, no UK institution has collected an NFT. After all, budgets are capped. Are museums willing to gamble on investing in an NFT when that money could go towards acquiring a painting?

However, it is a little-known fact that digital art has formed part of numerous public collections since the 20th century. Melanie Lenz, curator for digital art, architecture, photography and design at the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) tells me, ‘The first examples of computer-generated images acquired by the V&A were purchased in 1969.’ These lithographic prints were shown in one of the first ever exhibitions devoted to the relationship between the computer and the arts. Cybernetic Serendipity took place at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London in 1968.

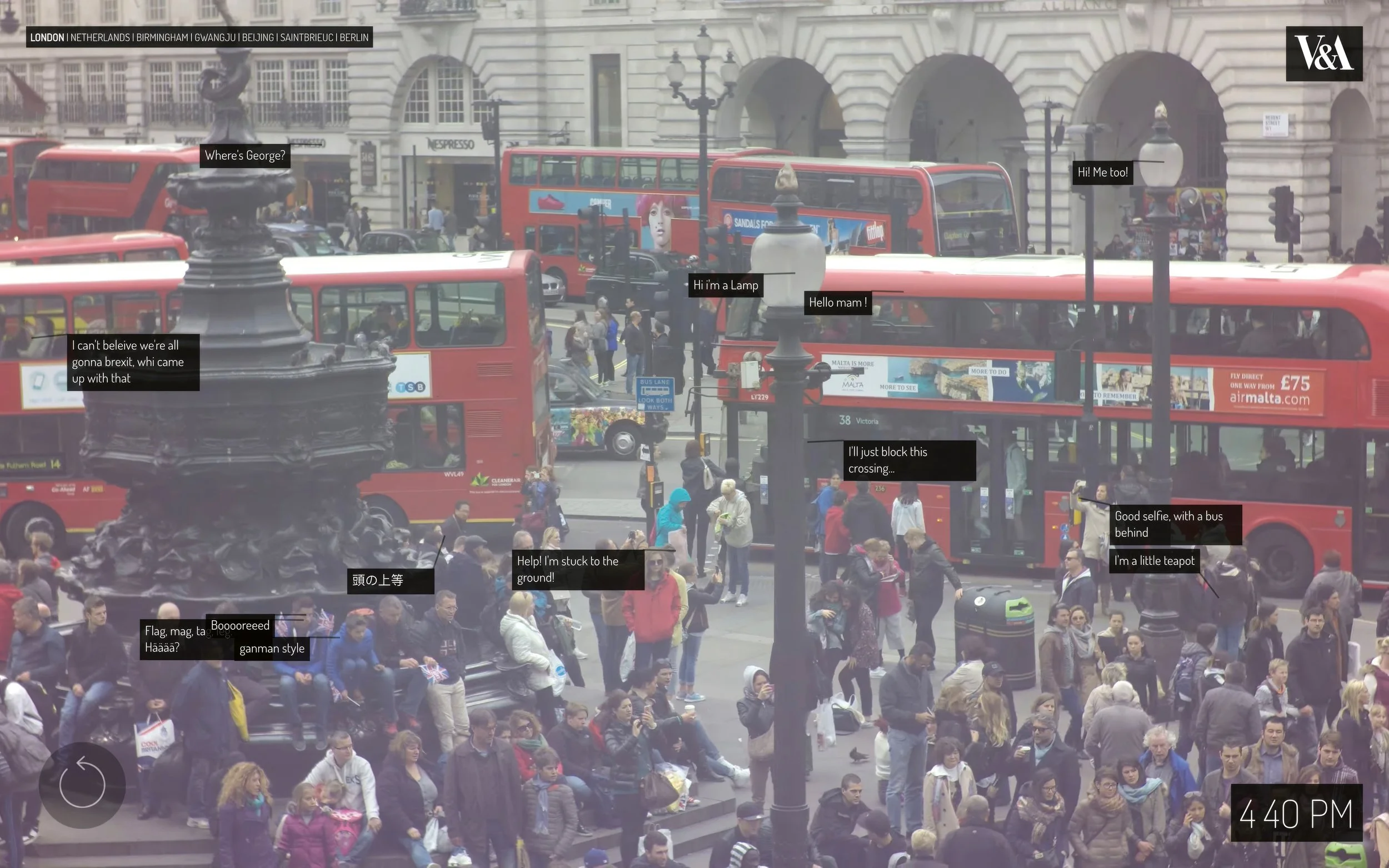

Kyle McDonald, Exhausting a Crowd. Image credit: Kyle McDonald

There’s a very long curatorial process even if you just want to donate a piece,’ says Alice. Usually, museums don’t want to diminish the quality of their collection. ‘In the NFT world, there’s no shortage of money and no shortage of people who want to donate their works,’ continues Alice, ‘So 99% of all NFTs in institutions have been donated. But now, finally, I’m beginning to see museums buying.’

Marlène Corbun, head curator at laCollection, a platform that seeks to bridge the traditional art market and the tech world, agrees, noting ‘it’s opening slowly – some are keener to innovate than others.’ And sometimes, it boils down to a thing as simple as whether someone likes what you do. Corbun, who has brokered several partnerships between public institutions and Robert Alice says, ‘I think they fell in love with the artwork. If I’d showed a different artist that day maybe the project would have never happened.’

She goes on to note that museums face other barriers to building their digital departments. Some institutions aren’t able to accommodate contemporary art curators, meaning this gap in staffing and expertise will reflect in acquisitions. Equally, she describes the process of storing a national collection’s first digital asset as, ‘a real hurdle’. These need to be kept in a crypto wallet, and with a public institution the process of setting one up becomes arduous, demanding verification from multiple government bodies.

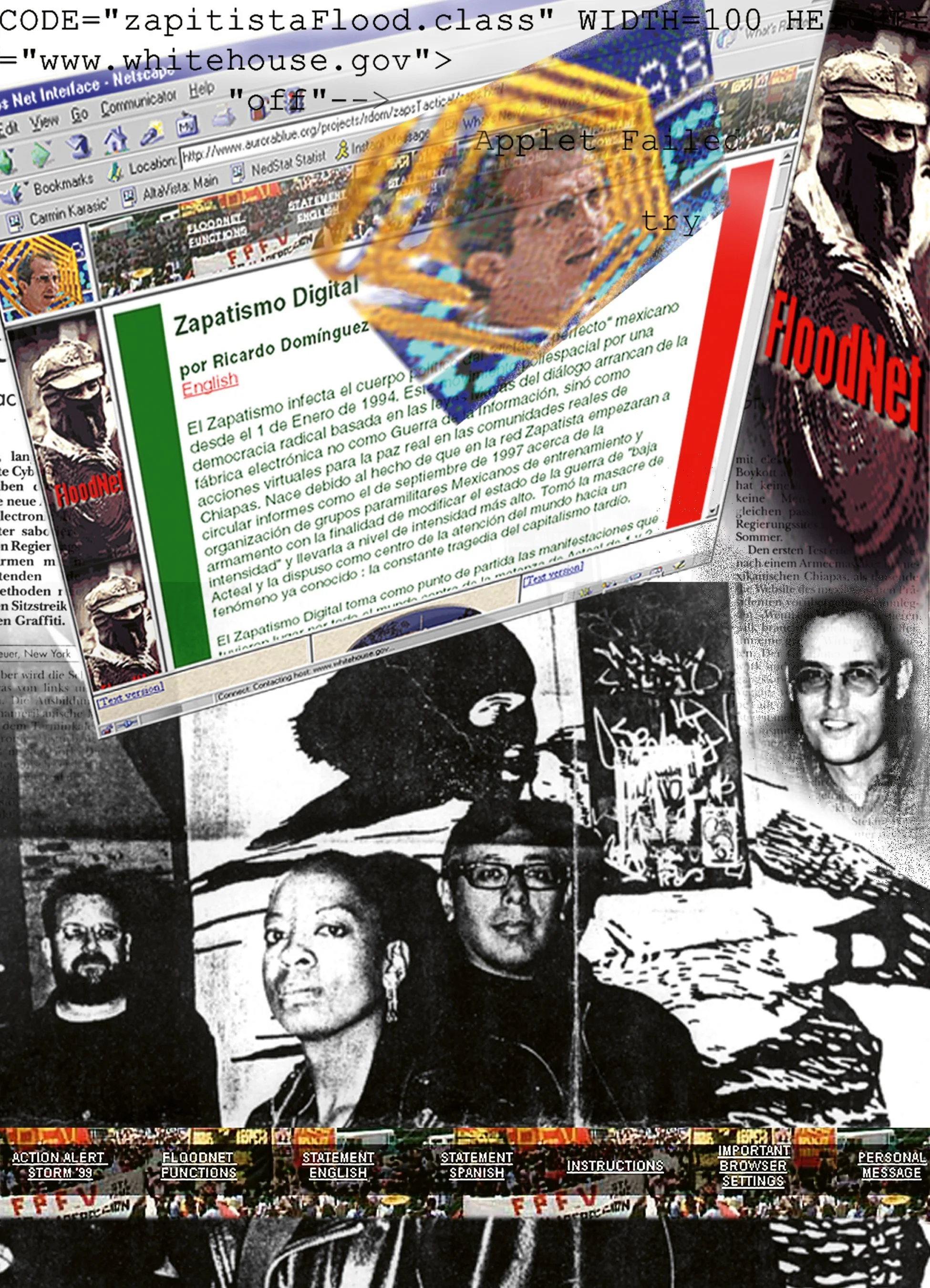

Electronic Disturbance Theater (EDT), FloodNet. Image credit: Carmin Kasaric for ECD. Courtesy of Carmin Karasic