Small Revolutions: Solidarity & Sound Systems in Southall

A poster for ‘Southall Kids are Innocent’, a Rock Against Racism fundraiser for people arrested during the 23rd of April 1979 Southall Uprising. Image credit: Gunnersbury Park Museum

Ranvir Singh Jagdev and Taranvir Singh Mathadu live in Southall, West London. They’re distant cousins who met at a wedding a decade ago. The pair bonded over a shared love of dub reggae legend Jah Shaka, and it wasn’t long before they founded their own collective, Vedic Roots, where they spin records on a sound system that Jagdev, a carpenter, built.

Vedic Roots setting up speakers. Image credit: Vedic Roots

If you’re unfamiliar with dub music, here’s a whistle-stop tour: pioneered as a genre in Jamaica during the late 60s and early 70s, Osborne ‘King Tubby’ Ruddock, Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry and Errol Thompson are usually credited with its invention. It’s a largely instrumental sound which takes existing reggae tracks and removes the vocals, while amping up the reverb and heavy bass. The dub sound system is traditionally homemade, comprised of huge and, crucially, very loud speakers.

When music is played through them, they vibrate so intensely that the bass morphs into something that you don’t just experience in your ears but in your whole body. It’s an all-consuming sensation no ordinary speaker can do justice to.

Dub arrived in London with the Windrush generation and stuck like glue. Today, Vedic Roots are just one of many dub collectives from West London. They regularly feature on the ‘West London Dub Club’ line-up, a (usually) Southall-based session hosting other sound systems and record labels often run by fellow British Asians, specifically of Punjabi Sikh heritage.

‘We’ve all grown up with music, and reggae was played on repeat’, says Mathadu. ‘I have three uncles who were DJs, and we had a sound system in the garage, where vinyls were always spinning.’ Mathadu was just fifteen when he went to his first dub night and witnessed Jah Shaka, his soon-to-be music idol, DJing a session in Southall. ‘I came out of that room enlightened; I’d never hear a sound like it.’

The bass morphs into something that you don’t just experience in your ears but in your whole body.

Vedic Roots performing at a Boiler Room gig at Southbank Centre. Image credit: Boiler Room

And yet for Jagdev, dub had a hint of the familiar. He plays the dhol, a large, double-headed drum used for the beat in bhangra, which creates the same vibrational bass as the dub speaker. ‘I’ve always liked music with a big bass line,’ Jagdev explains, ‘When you play the dhol, and you’re also surrounded by reggae music, something clicks in your brain, and you realise how well they fit. Bhangra is our folk music, created by the farmers. We like that beat and sound because it’s inherited from our ancestors. Reggae is the same – they were out there creating music with whatever they could find.’

The traditional rhythm of bhangra and reggae fit together perfectly; it’s a music partnership that’s been going for some time. Every track, for example, on Producer and DJ Bally Sagoo’s 1990 album, Essential Ragga, merges the bhangra and reggae beats. It was, however, the first-hand experience of a dub session in the early 2000s, also staring Jah Shaka, which sent Jagdev’s head spinning: ‘I remember all these Rastas just pulled up in a massive, batted van with these speakers.’ It was love at first sight and sound. ‘Seeing those speakers at that session, the 18-inch boxes, I knew I needed to build one of those.’

Tucked next to Heathrow, Mathadu and Jagdev’s home town of Southall is as far west as you can get within the confines of the M25. It has another name too: ‘Little India’. Southall is home to one of the largest populations of Punjabi Sikhs in the UK, though residents also include other Indian ethnicities and religions. But to call it ‘Little India’ doesn’t accurately represent the history of the town. From the post-war period to the latter half of the 20th century, it housed a mixed population of immigrants, mainly from countries that were once, or were still, under the governance of the British Empire, such as Ireland and the Caribbean.

‘We like that beat and sound because it’s inherited from our ancestors.’

A poster for ‘Southall Kids are Innocent’, a Rock Against Racism fundraiser for people arrested during the 23rd of April 1979 Southall Uprising. Image credit: Gunnersbury Park Museum

‘There was a lot of racism,’ explains filmmaker, artist and activist Shakila Taranum Maan, who was born in Kenya and raised in Southall. ‘We talk about a hostile environment now – but back then, it was ten times worse.’ She’s been part of the Southall Black Sisters, an anti-domestic abuse and racism not-for-profit supporting South Asian and Afro-Caribbean communities. She joined a couple of years after it was founded in 1979, following the death of anti-fascist activist Blair Peach during a demonstration against a National Front rally.

‘There was a very strong connection between the Caribbean and Asian community, partly because of the Southall Black Sisters. We shared experiences of racism, as well as domestic abuse within our own communities. We came to have a complete understanding of one another, as well as acknowledge how imperialism and colonisation both manoeuvred and operated within our communities. It meant we had complete self-determination. Being black was a uniting force.’

In talking about the early years of Southall Black Sisters, Taranum Maan paints a picture of energy and excitement: ‘politics fuelled everything we did – but this included parties too.’ She talks about seeing The Ruts, a punk band with dub, rock and reggae influences. ‘They were protest songs, truly inspiring, but their records were also hits.’ This pattern was repeating across London during this period – just think of the Brixton riots and The Clash.

‘Politics fuelled everything we did – but this included parties too.’

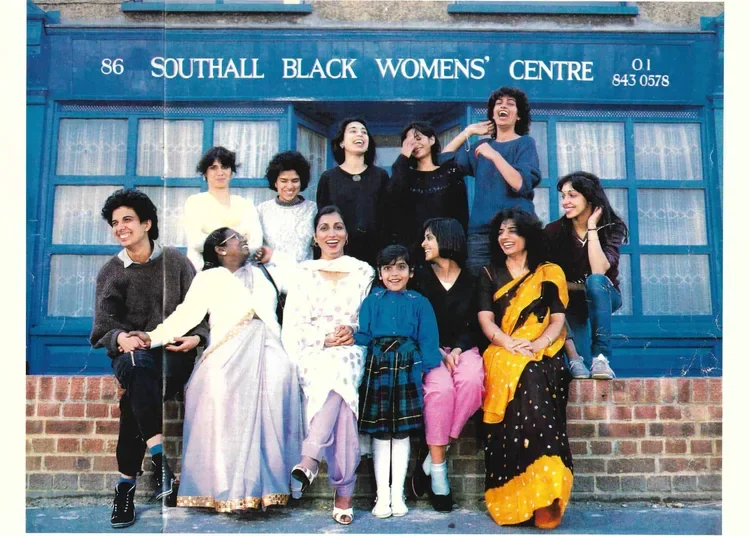

Image credit: Southall Black Sisters

The Southall Black Sisters is still an active and integral part of Southall’s identity, but Taranum Maan is more pessimistic about the environment they operate in today. ‘Identity politics, and too much involvement from government ‘monitoring’ has fragmented the community,’ she explains. ‘First being Black and being Asian was separated, then we were divided by country of origin – are you Bangladeshi, Pakistani, Sri Lankan? Then it changed to religion. It started very subtly, but it’s caused such a chasm within the community.’

For Mathadu and Jagdev, music continues to be the thread which holds their community together. ‘Dub gives you an education, and that’s brought people together here. You could go to Jah Shaka’s sessions regardless of sex, age, race. You saw so many characters and different types of people, but no one was judged, because to do that would be against the guiding mission of the music,’ explains Mathadu. He goes on to quote the lyrics from Misty in Roots’ song, ‘See Them-a-Come’: ‘see them ah come, but me naa run’. ‘It means to stand up together in unity, and don’t back down against an oppressor.’

A sound system built by Rana and Taran, at Gunnersbury Park Museum’s Sound of Southall gallery. Image credit: Matthew Kaltenborn

‘And there’s unity not just in lyrics, but in culture too – in Rastafari they refer to everyone as ‘I’, and in Sikhism, you’re meant to live in oneness with your neighbour. It’s a religion which encourages mixing with everyone, not shutting yourself off from the world,’ continues Mathadu. There are further parallels: they both place emphasis on clean diets and never cutting one’s hair. ‘It’s easy to connect with people when you believe the same thing, especially when it’s a message as simple as respect for others, and for yourself.’

Memorabilia from both Southall Black Sisters and Vedic Roots are currently displayed in Gunnersbury Park Museum’s current exhibition Peoples Unite! How Southall Changed the Country. ‘Southall is a microcosm,’ explains Senior Curator, Dr Tom Crowley. ‘The solidarity formed between communities pushing back against the National Front has lead to a pressure cooker of artistic expression, both past and present.’ Poetry, sculpture, film: the works on display listed by Crowley is long.

Southall’s current legacy is one of solidarity, of coming together over basic common ground, and getting creative with it.

Image credit: Boiler Room

‘I guess what's surprising is people feel this exhibit is pioneering or brave,’ he adds. ‘But it’s quite basic: we’re just retelling the significant recent history of our local boroughs. There's nothing radical about it, we’re not taking a conceptual risk.’

When you imagine a revolution you think of forces that transform cultures in an instant, people shaking off the weight of centuries overnight. But some revolutions happen at a gentler simmer.

Outside of West London, Southall has a history and culture that’s relatively unknown. And yet, this microcosm of the British experience, which uses music as a social glue, has played out across the country. Take Ska, product of the West Midlands, or the anti-Thatcherite post-punk sound of Sheffield. Southall may not exactly be leading the next national uprising, but it’s always had its hand in the game. But as Taranum Maan mentioned, there are cracks within the community. For now, Southall’s legacy is one of solidarity, of coming together over basic common ground, and getting creative with it. It’s worth reiterating Taranum Maan; ‘politics fuelled everything we did – but this included parties too.’

Peoples Unite! How Southall Changed the Country can be seen for free at Gunnersbury Park Museum until November 23rd. See their website for more information.

Learn more about Vedic Roots here.