The Silent Apprentices: Inside Nigeria’s Underground Prophecy Economy

A Nigerian street preacher. Image credit: Macnueldemi // CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

It’s a holy night in Benin. The church lights flare with anticipation. Everyone’s waiting for the prophet.

An inconspicuous young man, barely twenty, is hurrying back and forth from the prayer room. No spotlight follows him, but everything rests on his shoulders. Daniel* is an apprentice, one of many, labouring invisibly within this industry of faith.

Christianity is booming in Nigeria. From 2010 to 2020, Nigeria’s Christian population grew by 25%, according to the Pew Research Center. Charismatic, Pentecostal, and evangelical movements have exploded across Nigeria’s religious landscape, most visibly in cities like Lagos, Benin City and Abuja, where congregants fill megachurches by the thousands. The majority of Nigerians are Muslim, but the country now has the world’s sixth-largest Christian population. Furthermore, seven in ten adults believe in the efficacy of magic. Together, these strands create a curious new spiritual economy.

A religious gathering in Nigeria. Image credit: Andrew Esiebo // CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Everyone’s waiting for the prophet.

The growth is generated online, as well as in person. Churches draw views in their hundreds of thousands by live streaming sermons given by enigmatic preachers. Yet these charismatic ‘men of God’ can only move audiences with the help of apprentices like Daniel*, who assist—or, if you’re more sceptical, stage—revelations.

Prophetic scenes require elaborate planning, with rehearsed ‘secret’ cues. A former apprentice explained the system used by one prophet: ‘If he lifts his hand slowly, it means he wants a name. If he rubs his forehead, bring the list of those with financial cases. If he asks for silence, that means sickness.’

‘Most persons assume prophecy falls from above like rainfall. However, it is manufactured like bread,’ shares another ex-apprentice. He was nineteen when he joined the ministry. His village pastor told him he had ‘the eyes of a prophet’, and when a travelling evangelist visited, he was encouraged to follow him to the city.

‘Most persons assume prophecy falls from above like rainfall. However, it is manufactured like bread.’

What followed was a strange blend of spirituality and commerce. His days began before dawn with memory drills and scripture recitation, not for spiritual enrichment but to hone his rhythm of speech. Congregation members sent WhatsApp messages about their dreams, and after breakfast they’d transcribe them. I was eating rice under a mango tree. I saw a snake in my father’s compound. These dreams were sorted by theme—jealousy, stagnation, ancestral visions. Each corresponded to a pre-assigned interpretation. It is the apprentice’s job to match dream to interpretation, and respond to congregant’s morning messages.

A worship service at Word of Life Bible Church. Image credit: WLBC Media Team // CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

In the afternoons, they rehearsed prophecy like theatre. Apprentices played stock characters: the woman with the headache, the man seeking promotion, the mother praying for a male child. The senior prophet would walk in, eyes half-closed, voice trembling, and deliver revelations, training not to achieve truth, but effect.

A prophecy had to land like a punch and yet feel like an embrace, finding the correct balance of vagueness and authenticity. You didn’t say: You were born on March 3rd, 1982. That’d give away the effort apprentices took in gathering gossip from ushers, memorising prayer requests, monitoring Facebook posts. Instead, you said: Your birth month is early in the year… February or March? The subject completed the miracle for you.

‘If people were crying, that was ideal.’

Another apprentice described a system like stage lighting. ‘[The prophet] would give us signals: a cough meant “start the vision”. A pause meant “bring up the person whose name we discussed”. If the atmosphere felt cold, we waited. If people were crying, that was ideal — we moved fast.’

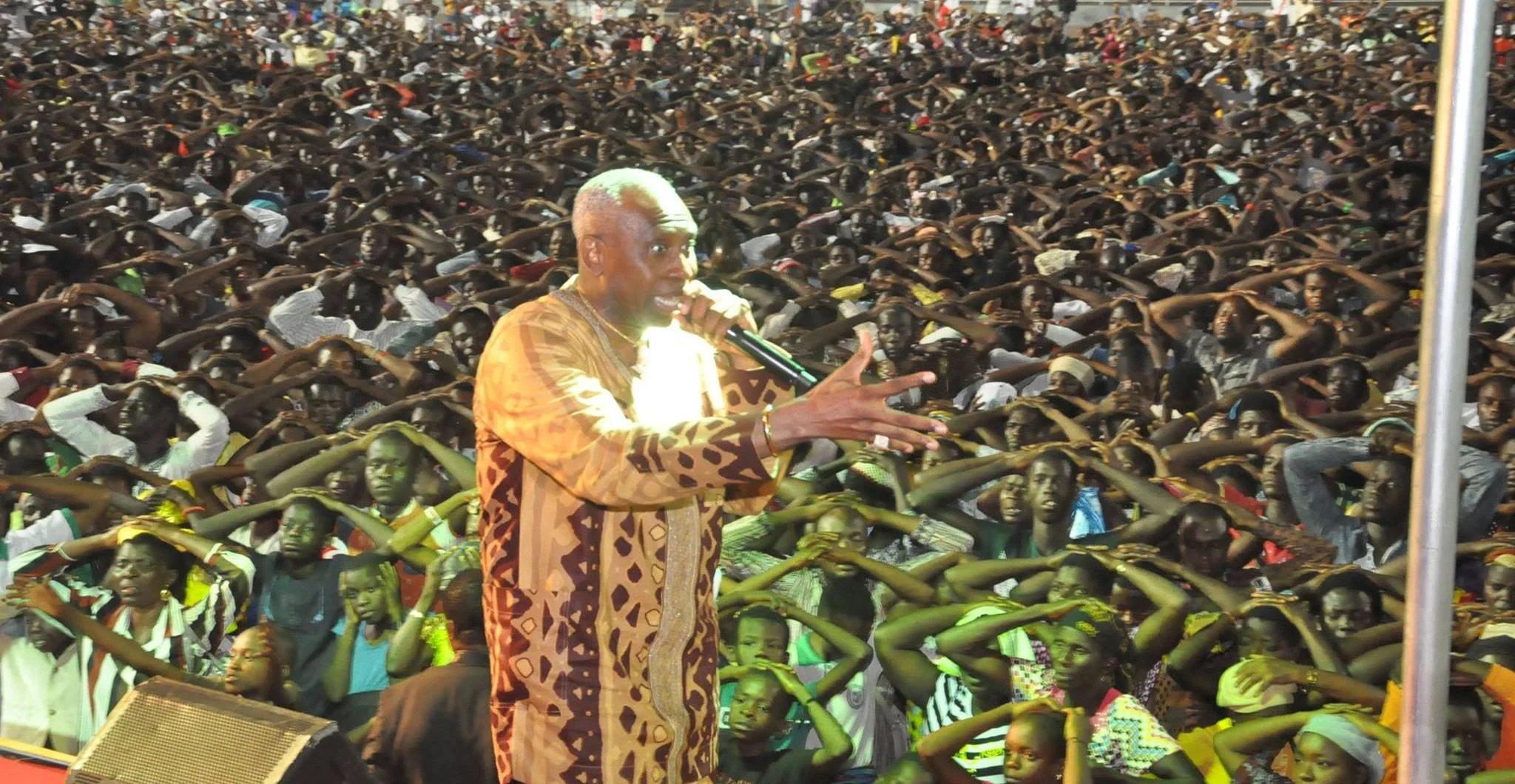

Pastor Ayo Oritsejafor ministering at the Warri Miracle Crusade in the Warri City Stadium. Image credit: True Nation // CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

One media technician operated lights to frame the prophet in a golden glow, cueing strings and pianos for dramatic effect. He ran testimonials like adverts during breaks, as well as maintained lists of congregants and their details. When a woman began crying in Row 6, he already knew her polyp history, fertility struggle, last failed IVF cycle. He whispered this information into the prophet’s earpiece, and the congregation called it revelation. ‘My job was to turn shock into spectacle’, he tells me.

Televangelist TB Joshua. Image credit: Jessicamarie145 // CC0 via Wikimedia Commons

And this spectacle is lucrative. According to Forbes, the televangelist TB Joshua was Nigeria’s third-richest pastor, with a net worth of $10-$15 million. After Joshua’s death in 2021, the BBC exposed allegations that Joshua’s disciples bribed people to pretend to be miraculously healed, and faked medical certificates ‘confirming’ their recovery. Religious scholars posit that, in a nation where formal employment and social safety nets are scarce, people are willing to invest what money they have into spiritual services promising miraculous success. Church members pay for private audiences and all‑night intercessions (performed by apprentices so the prophet can rest). ‘Breaking generational curses’ often comes with a price tag. Thus, one businessman sponsored a prophet’s car.

Despite this industrialisation of religion, some apprentices approach their work sincerely. ‘We helped God speak clearly,’ one apprentice says. Some succeed in ascending this industry’s complex production pipeline. They go from errand-boys cleaning the altar to studying the crowd, identifying their needs based off their clothes or body language. They watch and hope their work will be rewarded.

‘My job was to turn shock into spectacle.’

Speaking of rewards, they can be quite ostentatious. Most of these ceremonies are held at giant auditoriums or makeshift open-air sites off busy highways. Congregants come dressed in their very best, from well-ironed corporate wear to bright ankara robes with polished shoes. Prophets themselves dress to awe — white agbadas, tailored suits, robes edged with gold.

Another nineteen-year-old apprentice I spoke with told me that the secrecy of this industry is not abuse but privilege. ‘We are custodians of mysteries,’ he said. ‘The prophet carries mantle, but we carry the engine’. He believes his time will come, that he will someday speak on stage and people will listen.

This is a rare career. Like being a life coach or a salesman, charisma counts for more than certificates. For young people who want respect, or success, or simply a place to sleep, it’s an extraordinary opportunity to stand before a crowd and watch people literally collapse at your words. Unsurprisingly in such an environment, the potential for abuse and power-lust are considerable.

A former apprentice told me the first miracle he saw convinced him he was standing at the doorway of something eternal. ‘People fell,’ he said, ‘and I thought — wow, God knows my name by proximity.’ He stayed, not because he was deceived, but because he felt chosen.

‘He could not pray without hearing his former prophet’s voice. He says he felt ‘spiritually unemployed.’

Fierce competition means that an apprentice who leaves or loses their job is quickly replaceable. It’s also difficult to walk away from this role and return to an ordinary life without the divine promise of money, power and status. One ex-apprentice said leaving was harder than joining: ‘You spend years speaking as God,’ he says. ‘When you leave, silence feels like drowning.’ Without friends and the prophecy community, he felt exiled.

For Chisom*, leaving this community began in a quiet way. Small disagreements. Moments of clarity in the middle of a 4AM prayer chain (essentially a continuous group chat for collective prayer). For two years he’d fasted, prayed, slept under speakers during all-night vigils, eating only once a day. But when he left this world of intangibles, his real belongings comprised only a black nylon bag containing two shirts, a Bible, and a notebook. After leaving, the first thing he felt was guilt, not freedom. For months, he could not pray without hearing his former prophet’s voice. He says he felt ‘spiritually unemployed.’

A praying man in Nigeria. Image credit: Theindigochxld // CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

A former dream interpreter exited the industry after realising that his visions were not divine messages, but merely the result of exhaustion and fasting. ‘Sleep deprivation is its own prophet,’ he says. Others have more disturbing experiences of leaving. A young woman who worked as a revelation-writer told me she still receives threatening messages: You left your mantle behind. Power has cost — you must pay. You will return. She blocks new numbers weekly.

The prophecy economy doesn’t exist because Nigerians are gullible. World Bank statistics reveal that more than 30% of Nigeria’s population live in extreme poverty, and with school-leavers struggling to find employment, social media promotion and peer pressure give this industry an intense allure. In understanding this economy, technology is as important as theology.

‘I still believe in God. I just don’t believe in men who franchise Him.’

Some say it doesn’t matter if these visions are actually divine: that if hope is delivered, that’s enough. Across the country there are prophets and apprentices who genuinely hunger for God—and believers who worry that the trend of manufacturing online engagement will crowd out quieter forms of faith. Does this movement create worship that emphasises spectacle over salvation? Or might worshippers, growing tired of this status quo, return to more private forms of spirituality?

‘I still believe in God,’ one former apprentice says to me. ‘I just don’t believe in men who franchise Him.’

* Names marked with an asterisk have been changed at the subject’s request.