Welcome to the Manga Boom! Two Comic Book Pros Track Its Rise

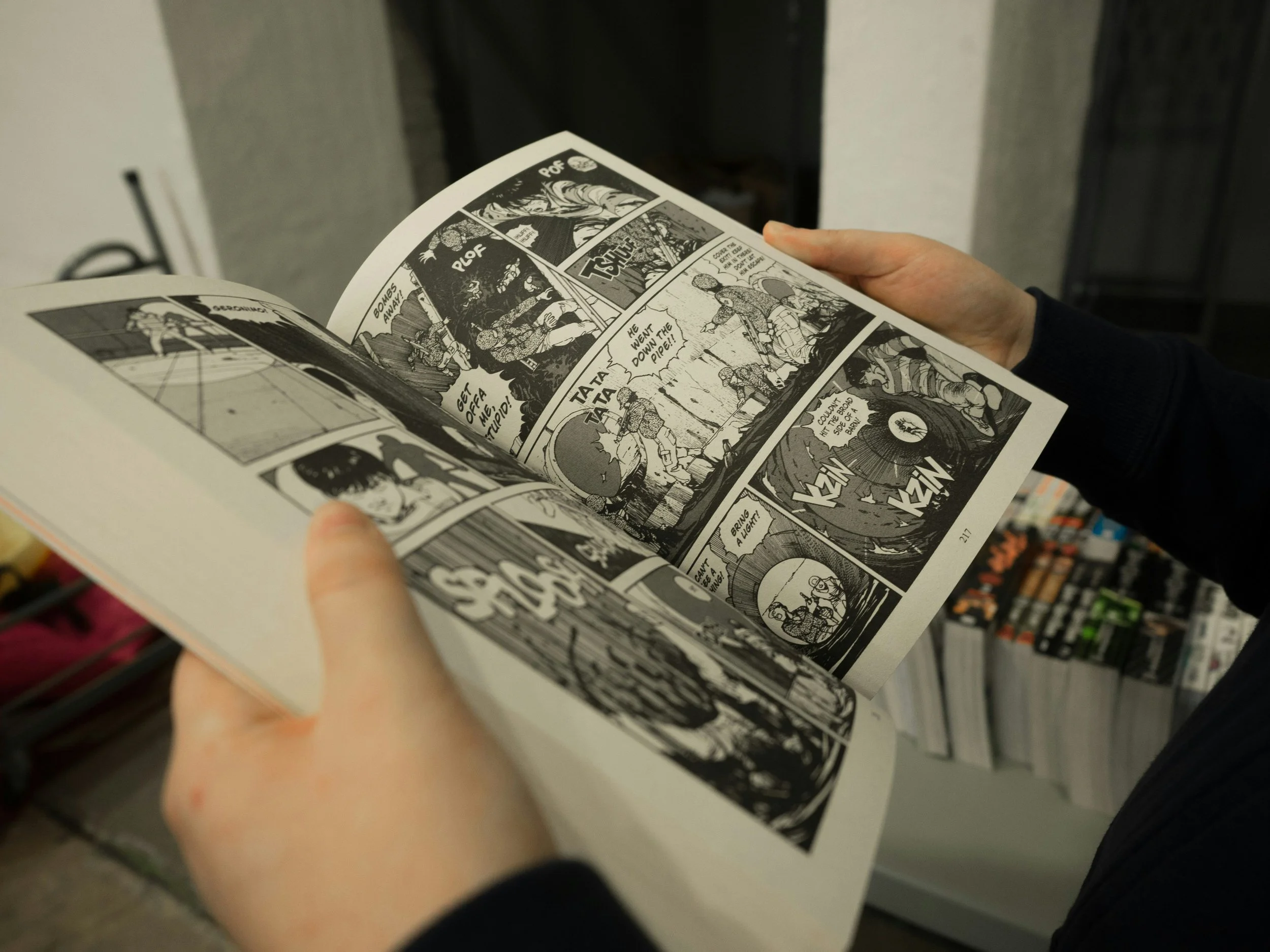

If, like me, you’re a frequent visitor to your local Waterstones, you might have noticed a slow metamorphosis in the manga section. Five years ago, it was probably just a dusty bookcase in the corner or stuffed in the chaotic scatter-shot of the graphic novels. Now, you’ll find a huge bay with fleets of titles given pride of place, surrounded by a milling mob of customers.

Manga has become a pop culture phenomenon in Britain, but what prompted this transformation? I caught up with experts at cult-entertainment retail chain Forbidden Planet, getting their insider’s perspective on what keeps manga readers coming back.

‘We’d never seen anything like this in any other group or category before: everyone wanted it.’

Established in 1978, Forbidden Planet supplies a global selection of comics and cult-entertainment merchandise. For the last decade Jamie Beeching has been in charge of supplying its stores with manga, while Vik Deluca, the assistant manager of Forbidden Planet’s new Camden store, has been on the frontline of cult retail for eight years.

‘I took it [manga] on around 2014 or 2015, and I’ve been growing it since then,’ Beeching shares. ‘Manga has now become such a part of the cultural conversation – so much of what we do as a company and what I do for it – that most people just know me as the manga buyer.’

Both Beeching and Deluca trace the UK’s manga boom to a single period: the COVID-19 lockdowns. People had time on their hands, and streaming services like Netflix and anime-streaming platform, Crunchyroll, made Japanese media more accessible than ever before.

This wasn’t a flash-in-the-pan trend, but the beginning of a cultural shift.

Beeching vividly recalls those months: ‘everyone seemed to spend their time watching anime, wanting manga, and then when we came out of lockdown, sales just went insane. We’d never seen anything like this in any other group or category before: everyone wanted it.’

Deluca, who ran his store’s mail-ordering and collection service during lockdown, recalls a turning point in customer requests. They were requesting increasingly obscure manga titles, sending his bemused team scrambling to track down copies.‘It was this perfect coming together,’ Beeching agreed. ‘The platform was ready, the people were ready, and then all of a sudden they had nothing to do.’

This wasn’t a flash-in-the-pan trend, but the beginning of a cultural shift. ‘If manga sales had just been driven by the pandemic, they would’ve gone away in time,’ Beeching points out. He argues that their staying power is due to the medium’s depth and imaginative escapism. ‘It’s coming from such a different culture, often set in fantastical worlds. And so many popular anime shows often revolve around themes of family and togetherness.’

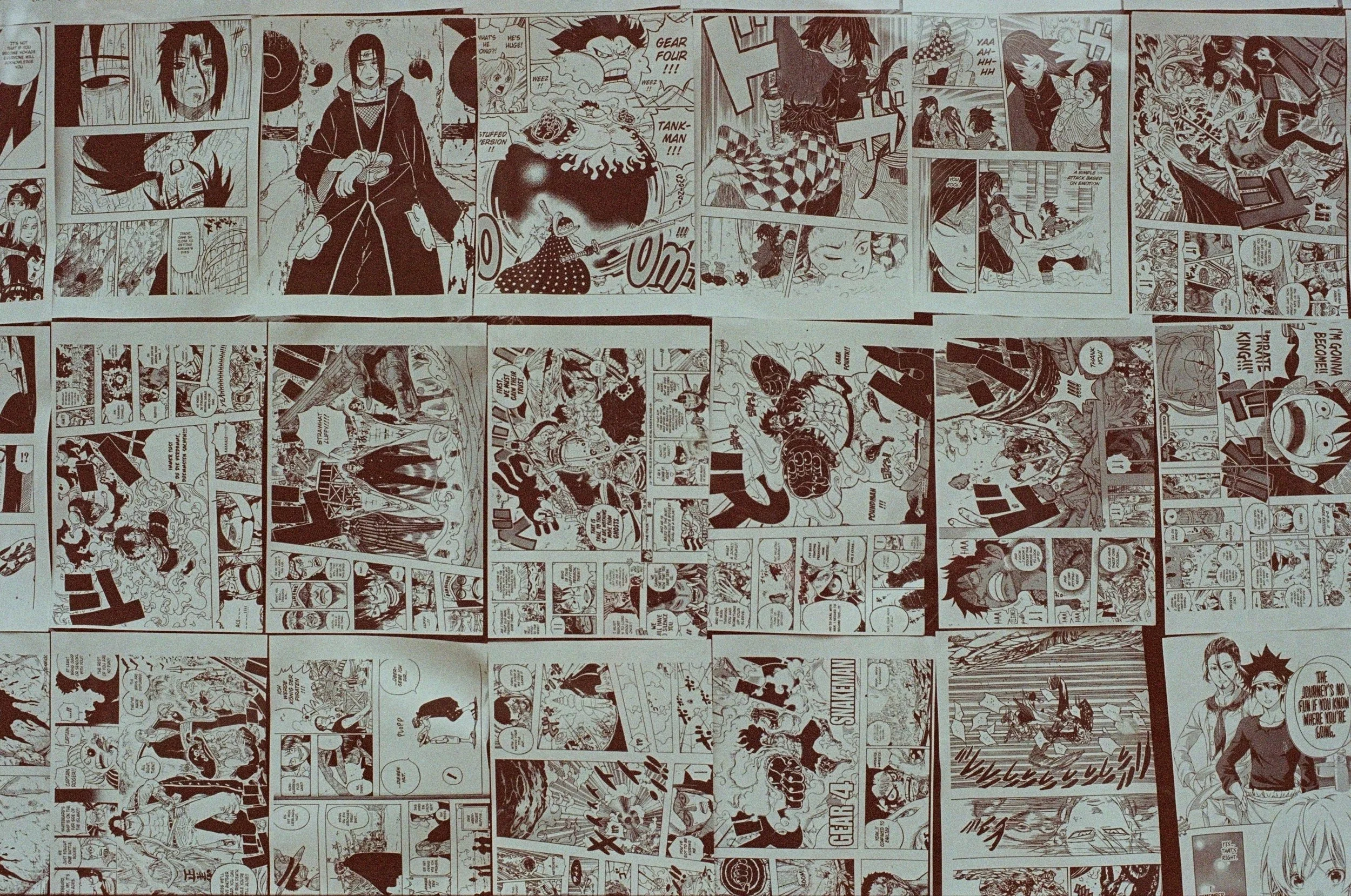

Calling manga a genre is like calling poetry a genre—it’s a medium that can tell any kind of story you can think of.

Deluca echoes these sentiments, describing the manga Naruto as being ‘Coronation Street but with ninjas.’ A bestselling shōnen series (meaning comics targeted at teenage boys) about a young ninja, Naruto features complex storylines and characters that play out like a grand soap opera. This, Deluca argues, is the series’ true strength: ‘you get to watch these characters over the years and grow with them.’ While ‘you can only do so much in a three-hour movie’, manga’s serialised format allows expansive plots to evolve over years and decades.

In Naruto, he explains, ‘the protagonist is such a well-crafted character, but every single character could easily have their own series and it’d do just as well.’ While Naruto, which was serialised for fifteen years and has inspired eleven animated films, has a particularly grand scale, any manga can enrapture audiences this way.

But calling manga a genre is like calling poetry a genre—it’s a medium that can tell any kind of story you can think of. Beeching and Deluca agree that it’s this diversity of content that gives manga so many different fans. Beeching adds that, while he can think of few Western titles dealing with transgender experiences, there are shelves and shelves of manga exploring this facet of life.

Manga’s serialised format allows expansive plots to evolve over years and decades.

And while Western comics primarily target male readers, manga has a wider readership. An example he cites is the slice-of-life series Komi Can’t Communicate, about a girl who suffers from a communication disorder, which won a major manga award and been adapted twice for television. Contrasting this with a Western publisher like DC Comics, he says, ‘As much as DC tries, Wonder Woman never sells as much as Batman or Superman. Yet Komi Can’t Communicate, a so-called “girl title”, was selling as much as a series targeted at male readers like One Punch Man.’

The runaway success of a title like Komi reflects how this medium can engage readers across demographics. Deluca adds that what ultimately draws readers to a particular series is the earnestness with which manga approaches its characters and themes. ‘Manga is so candid,’ he says. ‘There’s very little faff around it.’

The UK’s love affair with this medium may be intense, but it’s a relatively late arrival. In Europe manga has been part of the cultural conversation since the 1970s. Deluca remembers how, growing up in Italy, he could pick up manga at his local corner shop. ‘It was so present that I didn’t have to seek it out,’ he says.

‘Manga is so candid […] There’s very little faff around it.’

But time and globalisation have changed that, manga is here to stay in Britain, and Deluca and Forbidden Planet’s team are excited to nurture the medium. In the Camden store, they like to ‘cross-contaminate’ readers of Western comics and manga. The trick is learning a customer’s preferences, and then finding the right niche in manga to introduce them to.

‘There are things you can’t find in traditional Western comics, stories that you wouldn’t think of telling, and I’m as hungry for that as anyone else is.’

I decide to try him out myself. What titles, I ask, would he recommend to someone who doesn’t read manga at all? ‘I love this question,’ Deluca laughs. His three choices are 20th Century Boys, Naoki Urasawa’s long-running and ambitious adventure series; Tropic of the Sea, a fantasy story about a mermaid by Satoshi Kon (better known as the director of mind-bending anime films like Paprika and Perfect Blue); and Uzumaki, a surreal and twisted classic by horror-manga superstar Junji Ito.

For Deluca, showing readers new things is what he loves about this job: ‘If your audience would like to come and see us, whenever I’m here, it’s my favourite thing to do. Invite them over,’ he grins.

This is the heart of the matter: manga embraces everyone, and at its very best, it can cater to everyone too. ‘There is so much to find,’ Beeching says. ‘There are things you can’t find in traditional Western comics, stories that you wouldn’t think of telling, and I’m as hungry for that as anyone else is. It is something genuinely new to us.’